The Rhetoric of Perspective: Realism and Illusionism in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Still-Life Painting – Hanneke Grootenboer

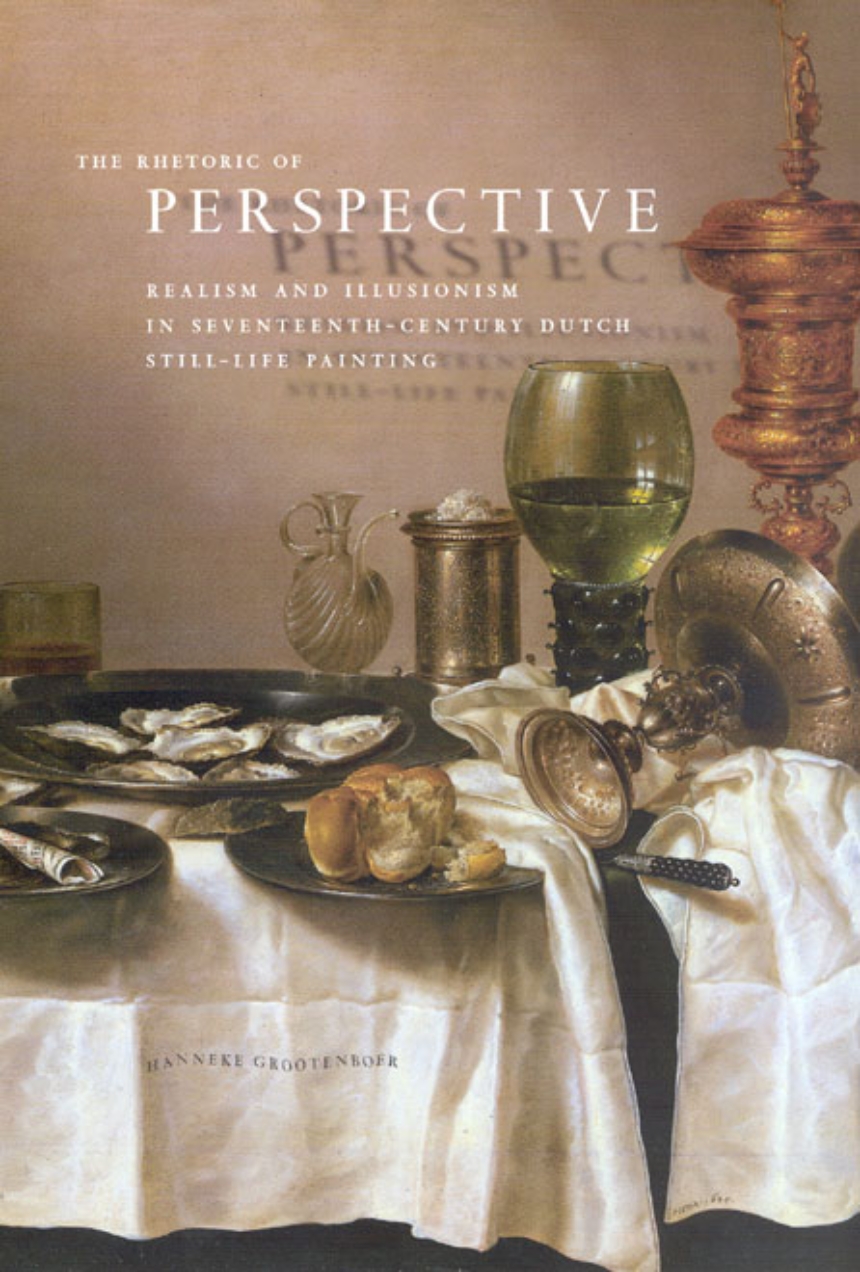

Warning, do not think this is a light Sunday read! So this book is a dense one, with a lot of reinterpretation of language to draw connections between disparate writings of art historians and philosophers. However, as I’ve been fascinated with the 17th century Flemish still life painter Clara Peeters, and it had a picture of a dutch still life painting on the cover, I had to commit to read this book fully. I over-ran my renewals at the library on this one but I made it.

Essentially she goes through many convoluted arguments to prove that painting is a form of thought. Well duh, I thought, ask any artist and you will get that answer. I think through art. Not while making art, well that too, hopefully, but through making art. That is why a painting is never merely an execution or illustration of an idea for me. It is an organic thing that shifts, changes and offers new discoveries along the route to completion. It is a discussion, which I initiate, but does not always go in directions I expected.

However despite not requiring her proofs, I gained a great deal from reading them. Of course I was familiar with anamorphism in painting (The Ambassadors (1533), Hans Holbein the Younger), however her exploration of its many iterations lead me to think about the possibilities of incorporating anamorphism into my paintings. Watch for that.

I was also enchanted with the idea of the painting looking back at us, the missing perspective which can be seen illustrated in paintings of reflective surfaces that sometimes depict the artist or the room beyond the painting.

I became fascinated with an idea, which might be my own mis-interpretation of her text, that the blank space behind a breakfast piece might function as an implied mirror. In the book she uses the example, The Holy Family (c.1513) by Joos Van Cleve, paired with Little Breakfast (c.1636) by Pieter Claesz. The former is an icon painting of Mary and the Christ-child at a breakfast table, while the later depicts breakfast items in the same order of the placement in the former; cup. knife, plate of food. However in the former the knife is placed as it would be if Mary, who faces out from the picture plane, had just used it, while in the later its placement is such to imply the painter, or the viewer had just used it. Looking at the table I realized that some of Clara Peeters breakfast pieces also resemble an inversion of that table, but with the knife switched to the side of the table that a right handed person, or Mary herself were she in the position of the viewer, would have placed it. The blank background (the author also studies the practice of painting the backs of canvases during the Dutch Golden Age) implies that the canvas surface, the barrier between us and the invented space of the picture is now on the other side of the table. Thus the breakfast piece paintings place the artist or viewer in the position of the Mary and Christ-child. If there were a mirror in that position the viewer would see herself looking back at someone in the position of the Icon at her breakfast table, thus giving quite a mental trip for a viewer familiar with religious painting: is that my reflection or am I the person that is being addressed by the person in the reflection? This led me to wonder if this reversal of view would have been recognized by the viewer, and would it have appealed to women specifically, asking them to recognize that holy state within themselves, without being as brazen as Albrect Durer when he takes the Christ pose in his Self Portrait at Twenty-eight (1500)?

This is not the authors argument, she is not interested in assigning symbolic meaning to the still-life, in her opinion there have been plenty of art historians who have examined still life looking for messages in the states and varieties of fish, flowers and fruit depicted, and plenty who have found Dutch still life resistant to meaning altogether. Her interest seems to be mainly that the blank space behind the still life, as an arrangement of apparently insignificant objects, is a deliberate relocation of the picture plane, drawing attention to the missing perspective of the painting which looks back at us. If this is the case perhaps Dutch still life painting marks a debate, and a transition in the perception of the place of power within a painting, that of the object painted or that of the painter/viewer?

In the tradition of Icon painting it was perceived that in some ways the depiction and the thing depicted were somehow connected, so the icon depicted as looking back at the viewer from the picture space could be seen and addressed by the viewer. The viewer could appeal to the persona depicted, who would then intercede with the deity. Icons were periodically destroyed throughout history for violating biblical proscriptions against idolatry, or the fear that people would worship the picture of the holy figure rather than using the images as tools to facilitate worship. So a still life painting which draws attention to the paintings surface as a barrier between a natural world and a super-natural world which returns our gaze is not really devoid of meaning, though they may not give their meaning clearly. Sometimes dangerous messages need to be hidden, as the author explores in her discussion of anamorphic art. Still life paintings of ordinary breakfasts, purporting to be un-observed, may be a form of iconoclastic art, spiritual art which incorporates the divine into the mundane, or may even debate the existence of a divine at all.

This is all inspiring for me when thinking about possible connections between the image of food in art and gender, now and historically. While it took me a while to make it through this book I think it is a worthwhile read. I am sure that there is enough here to sustain any number of interpretations and inspirations for artists working within the still life genre or within painting generally.