Welcome to the sixth instalment of a series of blog posts going more in-depth into the thoughts and ideas behind each of the paintings in the Earthly Delights series. The series is based on my experience navigating health and diet culture as a long term participant. You can read the full background by following the link to that blog post below:

Project Background: You can read more about the project background here.

Daily Recommended Intake (or Dietary Reference Intake, or Recommended Daily Allowance) – Return on Investment. Healthy eating doesn’t have to be expensive or time consuming, or so articles on eating on a budget claim. Canned and frozen foods are just as nutritious as fresh produce etc.

However for every ‘eating well on a budget’ piece of advice out there, one will find many more healthy diet plans that come with a healthy price tag too. The idea is you get back what you put in, and if you want to be skinny AND healthy, you’re going to need a specialized plan. Healthy eating, as promoted by health and diet culture, seems to be a bit of an exclusive affair:

At some point I decided I should be focusing on getting my body’s nutritional requirements, but didn’t want to risk gaining weight, so I was looking for a plan to do it within the lowest amount of calories possible.

This is why it is called health and diet culture, and not just diet culture. Because the pursuit of health has become tied to the cult of slim as it’s visible proof.

Enter my new salvation, (I will not name names here, but feel free to contact me if you want to know the name of the plan). This one was actually a set of menus carefully constructed to meet all of an individuals daily macro and micro nutrient needs within three different caloric levels (1500, 2000 & 2500). Significantly, there is not a caloric level which corresponds to the most common diet recommendation of 1200 calories/day, let alone the more extreme celebrity diets clocking in at 800 and 500 calories per day. The author specified that below 1500 calories per day one would require specialized medical instruction to meet their nutritional needs (mull that over). I didn’t have an objection to the plan itself (although at the time I thought 1500 calories was too many). I actually think the plan is quite an impressive effort, however the investment in terms of money and time is another matter. This investment is a problem with most popular ‘healthy’ diet plans.

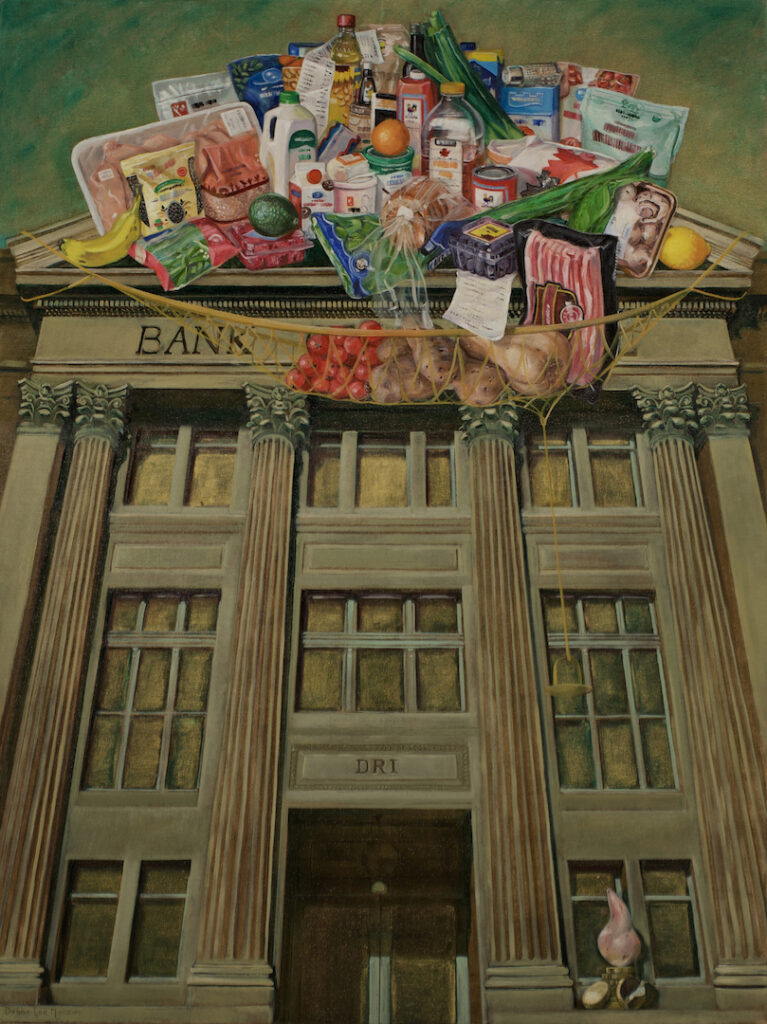

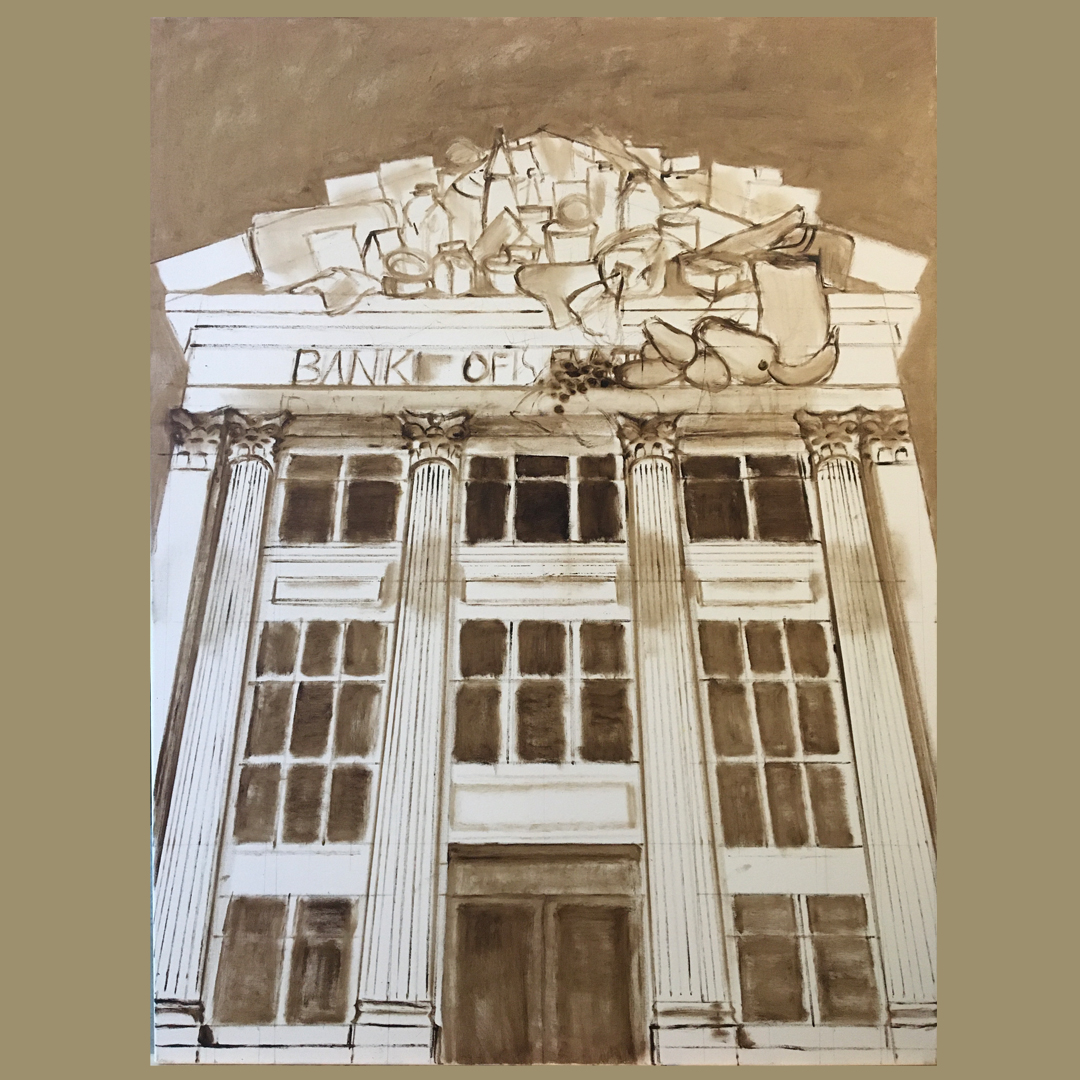

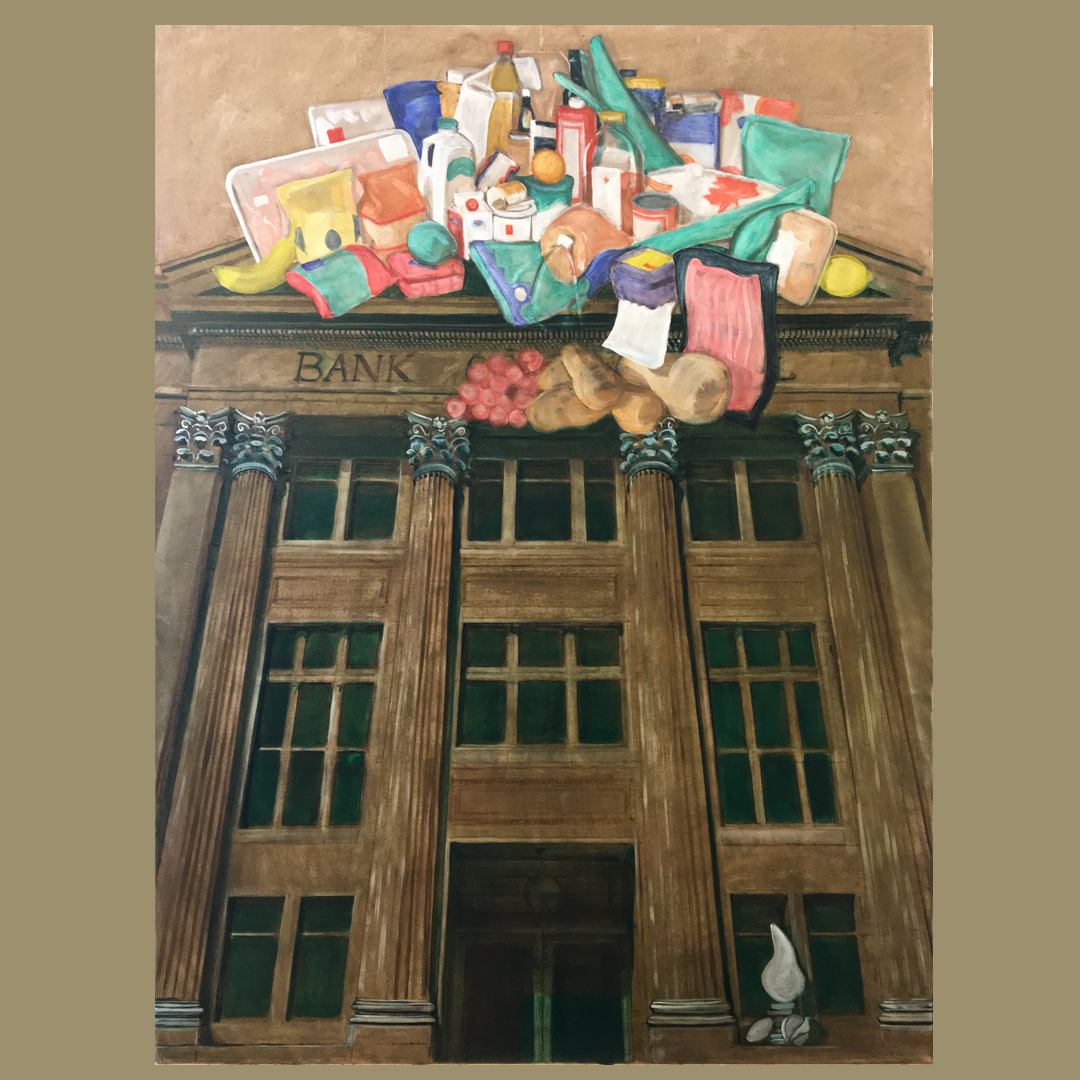

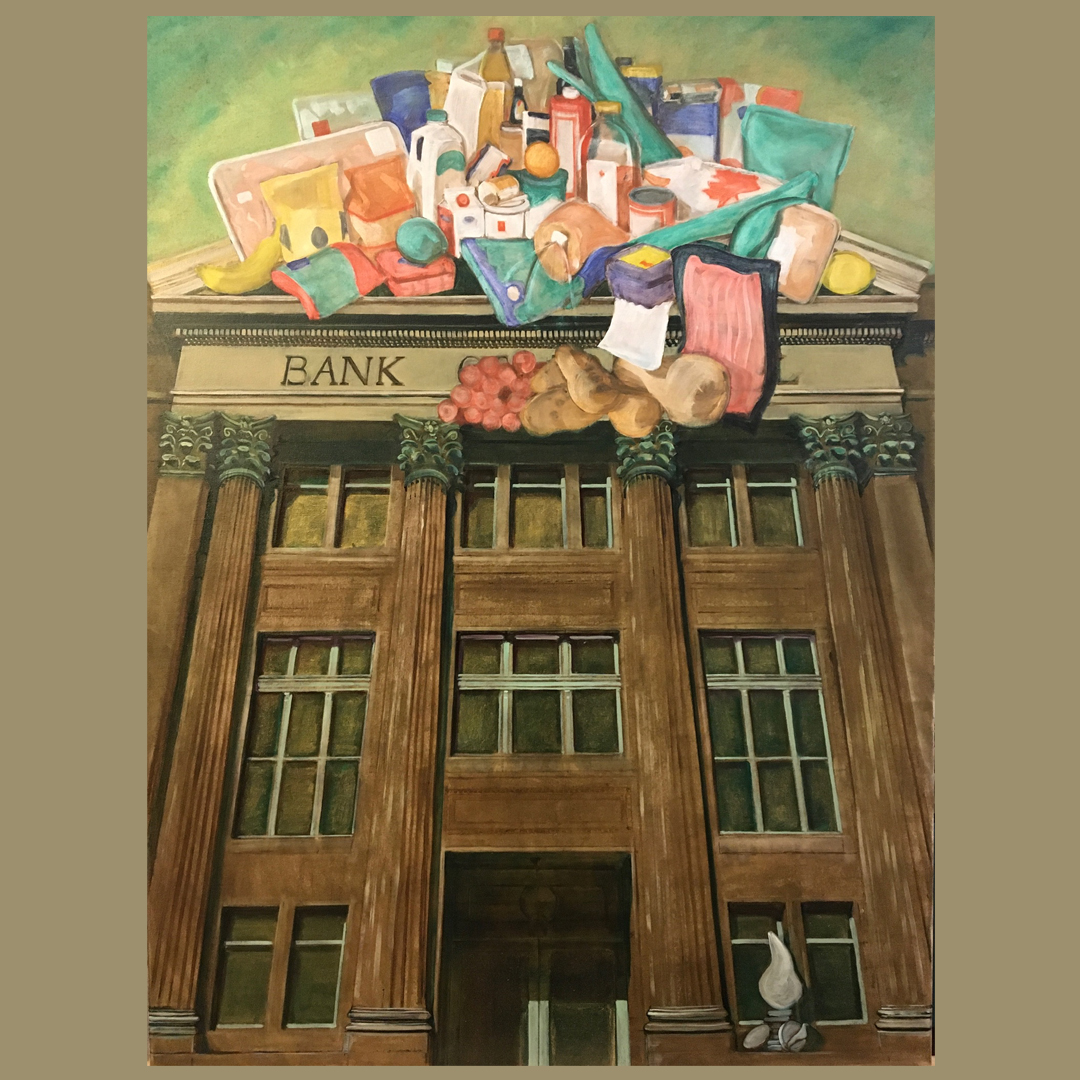

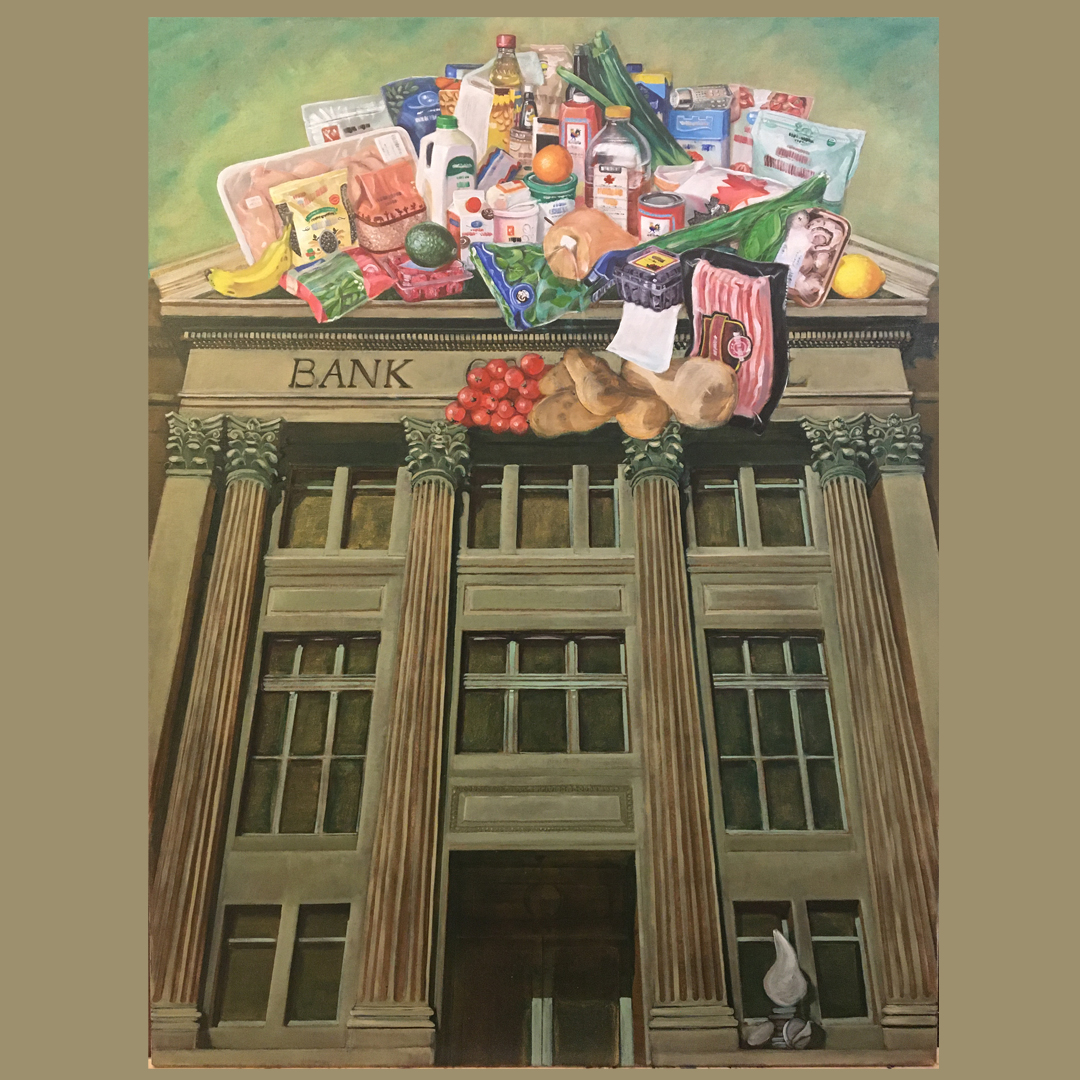

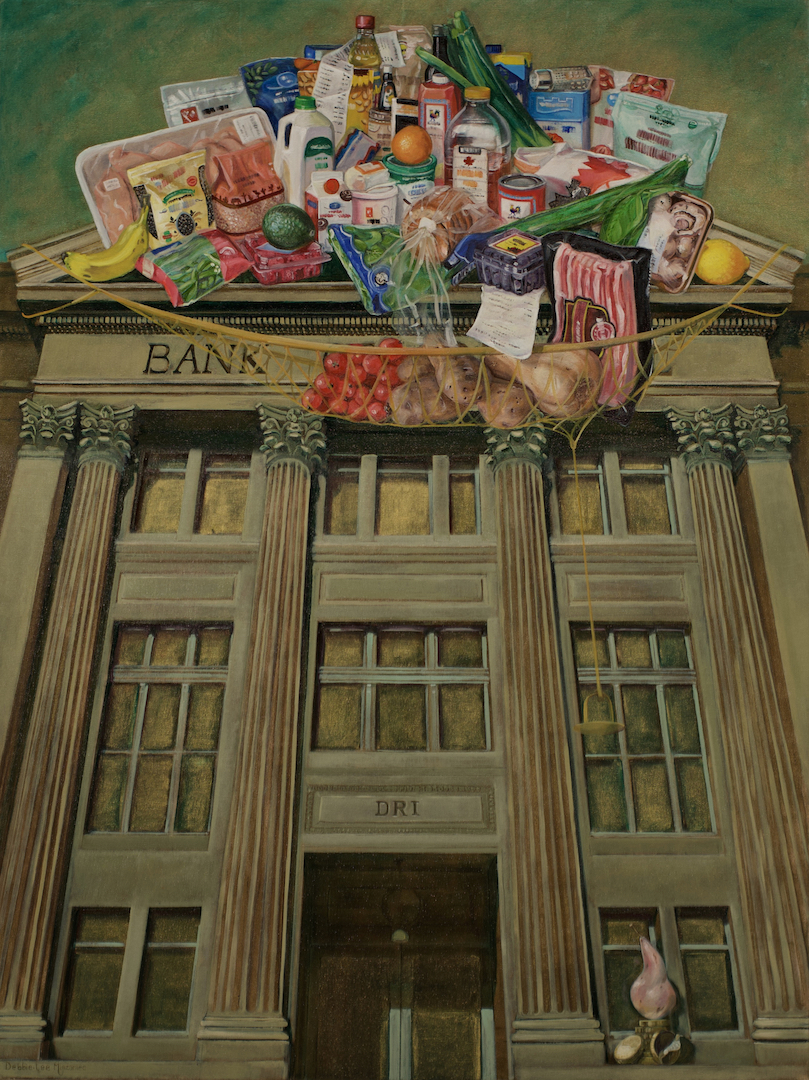

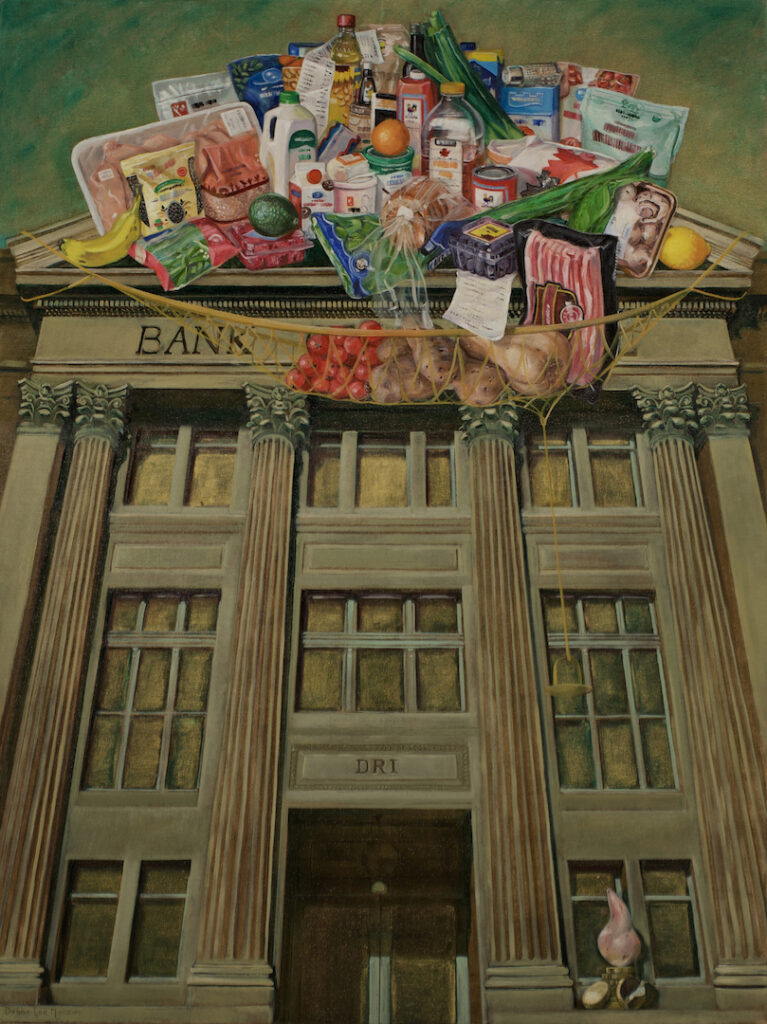

The food in the painting represents the ingredients (in purchased quantities) for a single day’s menu, at 1500 calories. Not that I would be eating all that food in one day, the menu might only call for a tablespoon of an ingredient, but one must purchase bags of buckwheat, barley or nutritional yeast as opposed to tablespoons. That is a lot of different types of food to be purchasing and storing, for one days meals, if I want complete nutrition within 1500 calories. (I challenge you to go price the entire still life, see what it comes to in your local dollars, and report back.) Yes, you will likely be using those ingredients in multiple menu (should you carry on with the plan), and things like cocoa powder and chia seeds will keep well in the pantry. However, it is typical of every new diet to not only have you invest in an entire new pantry of food, but clear your cupboards of all your old food. Often the new foods are expensive, exclusive, trendy, and difficult to source if you are not in a large urban centre with access to specialty markets and international food imports.

The setting for this super market banquet is a historic Bank of Montreal building on Calgary’s Stephen Avenue. Many of these heritage bank building are no longer banks: a few have been repurposed as high end restaurants and this one currently houses a Good Life Fitness. I wanted a bank as the setting, and I liked that in life as in art, health and diet were being coupled with wealth.

In DRI-Return on Investment I was interested in exploring several thoughts:

Are diets and dieting promoted by the food industry? Who gets wealthy from advising consumers to toss their inferior food before reloading with expensive ‘healthy’ alternatives with every new diet?

Are ‘healthy’ diet plans only for the comparatively wealthy, or is it that they are written by and geared toward the wealthy? According to an economic definition of middle class income as being between 75 and 200 % of Canada’s median household income after tax of $68400 in 2023, a middle class income is somewhere between $51000 and $137000. Working class incomes then would generally be below $51000 (although not necessarily). Most financial guides suggest a household grocery budget of no more than 15% of income for a family of 4. The average family (of 4) grocery spend is, as of 2023, about $313/week, or $45/day. That level of spending on food only fits current budget criterion for a household that, at $108507 CAD, has just crossed over into an upper middle-class income level. the pictured food here came in around $150 CAD, not including the dozen items I already had in my pantry. So taking into account the bulk nature of some of the ingredients, my guess is this would work out to about 60 – 65$ per day. For that same barely upper middle class household this would represent nearly a quarter of their budget. At the median income in Canada this represents over a third of household after tax income and 46% at the bottom end of the middle class income bracket. For a lower middle-class or working class family, not only is ditching a pantry of existing food financially wasteful, but the replacement cost for the proposed healthy alternative is a financially unsustainable way to eat

Are popular healthy diet plans sustainable? This still life presents the agricultural production of Canada and the world. Coconut, banana and avocado are commonplace in the modern Canadian diet. However Covid-19 and it’s supply chain disruptions presented the question of how sustainable or even accessible are ‘healthy’ diets that require a smoothly operating global supply chain providing international ingredients on demand to privileged markets? As supply was inhibited in countries used to near constant availability prices rose and accusations of gouging and profiteering flew. Sometimes the ability to pay did not matter as the goods simply weren’t there to be bought (looking at you toilet paper). However generally rising prices on limited supply means choice in diet becomes the prerogative of the even wealthier and more privileged. Meanwhile someone(s) happily made more money from less product.

Stay tuned for the next post exploring the time investment required by health and diet culture in DRI – The Most From The Least.